Gyuto knife vs santoku: differences that matter

Gyuto or Santoku first?

If you want one knife to cover the widest range of kitchen work, a gyuto usually takes it. That longer blade (most commonly 210–240 mm) gives you extra length for bigger product, longer strokes, and a steadier rhythm at prep. A santoku is often the easier starting point in a small kitchen, thanks to its shorter 160–180 mm blade and a calmer, more controlled feel on the cutting board.

That’s the clean headline for gyuto knife vs santoku—but the real choice lives in small things: edge shape, tip design, and which cutting technique feels natural when you’re moving fast. In practice, the knife that matches your motion gets used daily; the wrong profile becomes the expensive chef knife that just… lives in the drawer.

It’s also worth saying out loud: both are genuinely multi purpose. Both gyuto and santoku knives aim to be a versatile knife for daily cooking, just with different strengths and trade-offs.

Where did these knives come from?

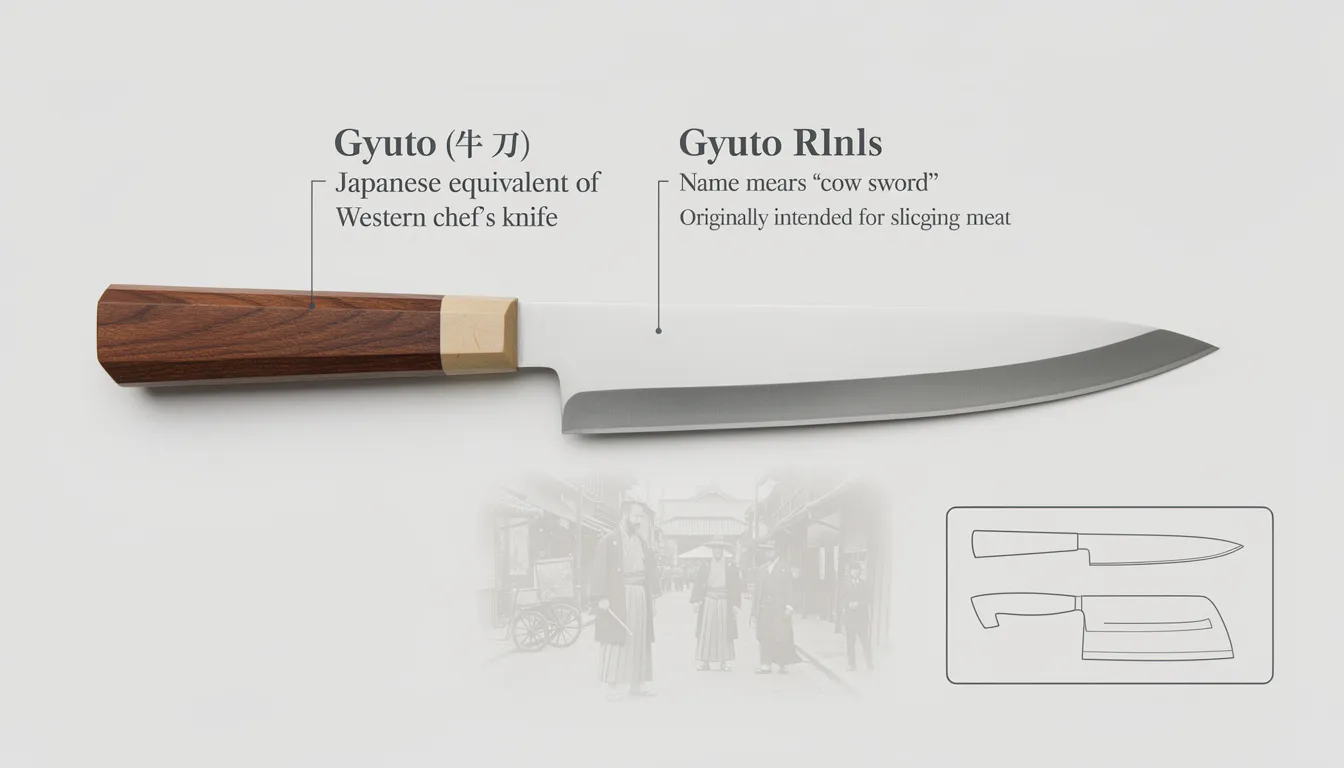

A gyuto is essentially Japan’s japanese equivalent of the western chef's knife, and it arrived during the Meiji era (a time when Japan was absorbing outside ideas at speed). Think of it as a Japanese re-interpretation of a French/German workhorse built to stay on a cutting surface all day. The name Gyuto literally means cow sword, and the intent was straightforward: slicing meat.

The santoku came later and grew up more at home. Santoku made its debut in the 1940s during the Shōwa era, developed for home cooks in post-war Japan. The name Santoku translates to “three virtues,” pointing directly to meat, fish, and vegetables as the core jobs.

That origin story still shows in real use. Gyuto geometry tends to assume more volume and longer strokes, while santoku geometry is happier in limited space, with smaller tasks, smaller batches, and lots of vegetables.

What are the key differences you actually feel?

Start with size, because it changes everything from confidence to board management. Gyuto knives are typically longer than santoku knives, ranging from 210 mm to 300 mm, while santoku knives usually measure between 160 mm and 180 mm. On a 210 mm gyuto, the extra length isn’t just “more blade”—it’s fewer resets per cut and more stable slicing.

Handling shifts with that knife length. Santoku tends to feel lighter and more maneuverable, which can mean more control for smaller hands or compact stations. For people who like the knife (and gravity) doing some of the work, that lightness can feel a bit “busy” on dense product.

Then there’s the tip geometry. A gyuto knife has a pointed tip—often a sharp tip—so it’s comfortable for detailed work and precise starts. A santoku uses a sheep's foot tip (sheepsfoot tip), which feels less aggressive near fingers and in tight angles, but gives up some tip precision.

How do edge profiles change cutting technique?

This is where the “it depends” gets real: slight curve versus flat profile. The gyuto generally has a gentle belly (a curved edge profile), which supports a rocking motion. The santoku tends to run flatter, favoring straight-down chopping and push cutting.

With a gyuto, that curve helps rock chopping feel smooth for herbs and quick mincing, especially at 240 mm where the arc stays predictable on the board. On many santoku knives, the flatter edge shape means more of the heel-to-midsection lands at once, which can feel like a clean “drop” rather than a roll.

Santoku knives shine in push cutting, especially for vegetable prep. That forward-and-down stroke keeps more cutting surface engaged along the edge, which is exactly what a flatter profile rewards. Put simply: santoku rewards neat, straight technique; gyuto rewards longer, flowing strokes.

What happens when slicing meat or fish?

A gyuto is often ideal for slicing meat, and the history basically confesses why. The pointed tip helps you start cleanly, and the longer blade supports calmer, longer pulls. For slicing meat, a 240 mm gyuto reduces that annoying “sawing” feeling because more edge stays in contact with the protein.

Santoku can absolutely handle proteins, but the shorter blade changes the approach. Santoku knives are built for broad home use—vegetables, fish, and meat—so they’re not delicate specialists. Still, when a roast, brisket, or big steak lands on the cutting board, that 160–180 mm blade more often pushes you into multiple strokes.

Fish is context-heavy. For sashimi and long single-stroke pulls, there’s a yanagiba or sakimaru for a reason (often 240–300 mm and single bevel). But for general fish breakdown and portioning, a gyuto can feel easier than a santoku simply because you get more reach and a finer tip for starting cuts cleanly.

Why does the santoku feel so natural for vegetables?

A santoku’s flatter edge and sheepsfoot-style tip are almost vegetable-biased by design. The flat profile favors push cuts and straight-down chopping, which works beautifully for carrots, cabbage, and peppers. And in a small kitchen, the shorter blade parks easily on a crowded board without turning meal prep into a spatial puzzle.

Santoku is popular with home cooks because the feedback is immediate: with a flatter edge, it’s easier to see whether you’re cutting square, and easier to correct when you’re not. That’s not “beginner-only”—it’s just honest ergonomics.

There’s also a safety/comfort angle. That lower, less pointy tip design can feel less stabby when you’re working quickly near your knuckles. The trade-off is that ultra-precise tip jobs—like scoring skin or trimming silver skin—usually feel more natural with a gyuto’s sharper point.

What does blade length change in real prep?

Blade length isn’t a status flex; it’s workflow. A gyuto knife is ideal for larger cuts and higher-volume prep because the longer blade length keeps a steady cadence. If you’re doing a restaurant-style run—ten onions, a case of herbs, a tray of chicken—210–240 mm gives you fewer interruptions and more efficient cutting.

Santoku knives are better suited for compact kitchens thanks to their shorter blade length. On a small board or narrow counter, 160–180 mm feels controlled, and the tip stays out of trouble. It’s also easier to store in short drawers or on smaller magnetic racks.

Here’s the nerdy workshop truth: longer blades amplify small geometry choices. A 240 mm gyuto with too much belly can “skip” on push cutting, while a very flat long knife can feel sticky if you try heavy rocking. With santoku, the shorter span tends to hide those extremes.

How do steel and forging choices show up here?

Both gyuto and santoku knives show up in similar steel families, from high-carbon steels to stainless steel and stainless steels. So the format alone doesn’t decide edge retention or toughness. The real story lives in heat treatment and how thin the blade is behind the bevel (and whether it’s a double bevel edge in common Western-friendly setups).

Japanese knives often run harder steel than many Western knives, which can hold a crisp apex longer—but it also asks for better habits on the cutting board. In 2026 talk, “better” is rarely just hardness; it’s whether the geometry actually supports that hardness without chipping when real life happens.

From a blacksmith’s perspective, construction details can also carry tradition you can see. Tamahagane is a historic material tied to traditional steelmaking, while wrought, fibrous iron (often used as cladding) brings a distinct feel in hand-forged laminations. Damascus and layered “Damascus-style” builds add pattern, but through food the grind still does most of the work.

In our shop at MG Forge, the most repeatable micro-decision is matching grind to cooking style: a slightly thinner midsection for vegetable-heavy cooks, or a touch more “meat” behind the edge for people who hit dense squash and do lots of board contact. Same knife category, different daily reality.

What about maintenance and sharpening in 2026?

Care is the part nobody photographs, yet it decides whether a kitchen knife stays fun. Both gyuto and santoku require similar handling: hand wash, dry immediately, and don’t let the knife live wet in a sink like it’s paying rent. If you want minimal maintenance, stainless steel makes daily life easier—but it still benefits from good habits.

Japanese knives respond best to Japanese whetstones. That’s not a collector hobby—just a stone setup that cuts hard steel predictably. A basic pairing (a medium stone for sharpening and a finer stone for refinement) gets most people there; the cutting technique on the stone matters more than the logo.

Boards are a bigger deal than most people want to admit. Use wooden cutting boards when you can, because they’re kinder to thin edges. And don’t go through bones or other hard materials—harder steel doesn’t “bend and forgive,” it chips when it meets a chicken bone or a frozen edge.

Where do people choose wrong?

Most wrong picks come from ignoring kitchen reality and personal preferences. Choosing between a gyuto and a santoku depends on prep volume, kitchen size, comfort, and what motion your hands default to. If you’re in limited space with a tight cutting board, a 240 mm blade can feel like parking a long car in a short garage.

Another mismatch is expecting one profile to behave like the other. Gyuto supports rocking because of its curve; santoku’s flat profile prefers push cutting and straight-down chopping. If rock chopping is your habit, a very flat santoku can feel like it “thunks” into the board instead of flowing.

A small workshop story repeats every year. Someone asks for “a santoku that rocks like a chef knife,” then later admits the real job is 80% vegetables and weekday dinners. In that scenario, a santoku with a modest belly can work, but a 210 mm gyuto often becomes the calmer daily tool—especially when you want one chef knife to do almost everything.

How to pick a first japanese knife?

A good first japanese knife doesn’t need to be complicated; it needs to match daily cooking habits. Since both gyuto and santoku are multi purpose, the decision can be reduced to two questions: how much cutting surface do you actually have, and what motion do you actually use. For many people, it’s basically gyuto knife vs santoku as “longer reach” versus “compact control.”

A practical checklist helps:

Kitchen size: smaller counters often favor 160–180 mm santoku.

Prep volume: bigger batches often favor 210–240 mm gyuto.

Motion: push cutting and straight chops favor santoku; rocking favors gyuto.

Typical food: lots of vegetables points toward santoku; lots of meat points toward gyuto.

When the goal is a single do-it-all chef knife, a 210 mm gyuto often hits the sweet spot. It feels close to a Western style chef knife (sometimes with a western style handle), but with Japanese thinness and precision. When comfort and more control matter more than reach, a 165–180 mm santoku tends to feel immediately friendly.

If you want a simple default without overthinking your first Japanese knife: 210 mm gyuto for general prep, or 180 mm santoku for small kitchens and vegetable-heavy cooking. From there, specialty japanese knives—petty for small work, deba for heavier fish tasks, yanagiba for sashimi—can come later without regret. (And yes, bunka knife exists too: similar sizing to santoku, with a more angular tip.)

Which is better, Santoku or Gyuto?

Neither wins universally; the right knife depends on cooking style, prep volume, kitchen size, and your cutting technique. Gyuto tends to handle larger cuts and higher-volume prep better because it’s longer (often 210–240 mm). Santoku tends to feel easier in compact kitchens because it’s shorter (usually 160–180 mm) and very controlled on the cutting surface.

What are Gyuto knives good for?

Gyuto knives are built for classic chef knife work: slicing, cutting meat, slicing meat cleanly, chopping vegetables, and quick herb work (including dicing onions and other prep). The pointed tip helps with precision tasks, and the longer blade supports longer, steadier strokes. They’re a common pick among professional chefs because they’re close to the most versatile knife most kitchens will ever need.

Do professional chefs use Santoku?

Yes. Many do, especially for vegetable-heavy prep and tight stations where a shorter blade feels safer and faster. Santoku knives are light, maneuverable, and naturally suited to push cutting and straight-down chopping. In plenty of pro setups, it’s a second knife next to a longer gyuto—different tools, different moments.

Can you rock with a Gyuto?

Yes. Most gyuto have a slight curve that supports a rocking motion, and rocking usually feels best on 210–240 mm where the belly and blade length create a smooth arc on the cutting board. If a gyuto is ground very flat, you may prefer push cutting for cleaner contact and less “see-saw” on the edge.

How do gyuto and santoku choices map to cutting workflow and handling?

Across knife manufacturers and knife makers, the most consistent divider is that a gyuto’s longer knife length supports efficient cutting with longer strokes and steadier rhythm, while a santoku’s shorter format emphasizes compact control, safer board management, and easier transferring food with its wide blade; both remain a versatile knife, so the right knife depends on space, prep volume, and whether rocking or push cutting feels more natural, and many professional chefs keep both patterns in rotation for excellent performance (including in small-shop builds such as MG Forge).