Japanese santoku knife: size, control, and daily use

What makes a japanese santoku knife so practical?

A japanese santoku knife is the blade a lot of people grab when they want one tool that can handle most daily prep without drama. It’s built for three jobs—slice, dice, chop—and that’s literally in the name: “Santoku” translates to “three virtues,” referring to its proficiency in chopping, slicing, and dicing.

In real use, it’s meant for vegetables, fish, and boneless meat, without forcing you into a specialist workflow. The santoku knife is designed for slicing, dicing, and chopping meat, fish, and vegetables, so you can move from onions to salmon to chicken thigh in the same session and keep momentum.

Worth adding: santoku knives are often recommended as multipurpose knives for home cooks and are more commonly found in Japanese households than gyuto knives. That popularity isn’t hype—it’s size, control, and how the edge meets the cutting board in everyday cooking.

Why does santoku feel “controlled”?

Two traits explain that calm, planted feeling on the cutting board: height and balance. The wide blade of a santoku knife gives good knuckle clearance and makes it easy to move chopped food off the board, so you’re not hunting for a bench scraper every two minutes.

The second piece is balance. The typical balance point of a santoku knife sits near the bolster or heel, which keeps the tip from feeling floaty and helps the edge track clean through carrots and cabbage.

In the forge, tiny decisions show up fast: a few grams in the tang, a slightly thicker spine behind the heel, and suddenly the knife “falls” into food differently. That’s where craftsmanship quietly turns into precision.

What blade length works best?

Most santoku live in a sweet spot: shorter than a western chef's knife, but still long enough to do real prep. Santoku knives typically have a blade length of around 170mm (6.7 inches), a practical middle ground between maneuverability and cutting surface.

That doesn’t mean every Japanese kitchen should lock into one number. A smaller cutting board and tight counters often feel best with 165–180 mm, while batch cooking can make 180 mm feel more efficient for longer slicing strokes.

This is also why, in a compact kitchen, a santoku knife can reduce the need for specialized knives—it covers a lot without demanding extra space.

How do weight and balance change cutting?

Your hand notices grams before it notices steel names. A standard santoku knife weighing around 120g to 200g is generally easy to use, especially when long prep sessions start adding up.

Also, the weight and balance of a santoku knife change how safe and accurate it feels. Two blades can share the same blade length and still feel totally different because of handle shape, tang construction, and where the mass sits.

Put simply: choosing a santoku knife that feels right in your hand is crucial. It’s not only comfort—control is safety, and safety is speed.

What does the edge geometry actually do?

Santoku has a recognizable profile: shorter blade, flatter edge, and a tip that doesn’t exaggerate the curve. The santoku knife typically has a flat edge, which favors straight-down chopping and clean, predictable cuts.

At the same time, the edge isn’t always ruler-flat. The santoku knife’s slightly curved edge allows gentle rocking, so herbs and garlic can be finished with a light rock instead of a full chop-only routine.

Another detail that matters on wet foods: many santoku knives have a Granton edge, those small indentations that reduce sticking so thin slices of potato or cucumber release more easily.

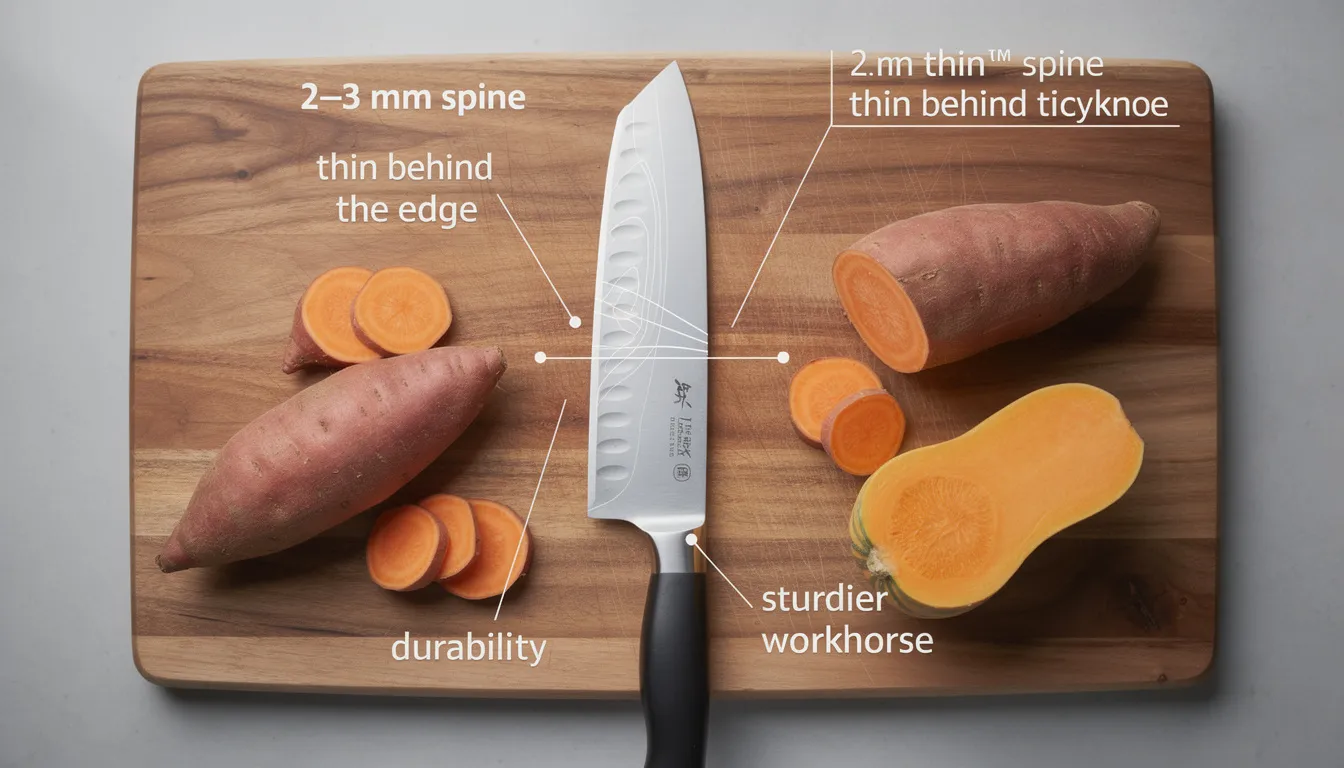

How thick should the blade be?

Thickness is the quiet compromise between “laser” and “workhorse.” Blade thickness determines the balance between sharpness and durability, and you feel that trade-off the moment you hit harder produce like sweet potato or squash.

For typical home cooks, a blade thickness of about 2mm to 3mm is recommended. Thinner can feel incredible, but it may demand more careful technique and board contact.

Here’s the hitch: a santoku can keep a 2–3 mm spine and still be ground thin behind the edge, so “thickness” alone doesn’t tell the full story. The grind does, and a thick blade isn’t automatically a tough blade if the geometry behind the edge is delicate.

What about carbon steel versus stainless steel?

This is the choice that shapes the whole ownership experience. Common blade materials for santoku knives include carbon steel and stainless steel, and both can be excellent—just with different habits.

Carbon steel santoku knives are favored by professional chefs for their exceptionally sharp cutting edge and long-lasting sharpness after a single sharpening. That extra bite can feel almost “sticky” on tomato skin, in a good way.

The trade is daily care. High-carbon steel delivers standout sharpness, but it’s more prone to rust if the knife sits wet after you cut meat, fish, and vegetables and then walk away “for a second” (famous last words).

When does stainless steel make more sense?

A lot of serious cooks still pick stainless because life is busy. Stainless steel santoku knives are rust resistant and easy to maintain, which matters when prep gets rapid and dishes pile up.

This isn’t only about rust, it’s about lowering friction in your routine. Stainless steel options are easier to care for, so you can wash, dry, and put the knife away without a full steel ritual.

In 2026 it’s also normal to own both: a stainless santoku as the weekday driver, and a carbon steel blade for the sessions where sharpening feel and edge feedback matter.

Is Damascus just for looks?

A Damascus santoku can be both aesthetic and practical, depending on how it’s built. Damascus steel santoku knives are known for their wave pattern and high-end look, while still aiming for a balance of sharpness and durability.

In traditional Japanese knife talk, it helps to separate terms people mash together online: folded patterns, forge-welded cladding, and layered construction aren’t identical. In a shop like MG Forge, those choices often connect to workflow—how the billet moves under the hammer, how heat treatment behaves, and how the final polish reveals structure.

Damascus looks great, sure—but it’s worth knowing what’s under the pattern and how the blade is actually ground.

How does santoku compare to other knives?

This comparison never dies because santoku sits in the middle of so many roles. The santoku knife is often compared to the chef knife, utility knife, and vegetable knife, but each one nudges your cutting styles in a different direction.

A few practical matchups you’ll actually see in kitchens:

Santoku vs gyuto knife (chef’s knife): gyuto often favors longer strokes at 210/240 mm; santoku stays nimble around 165–180 mm.

Santoku vs petty (utility): petty is for in-hand detail; santoku is for board work and volume.

Santoku vs bunka/kiritsuke: those tips can feel more aggressive for precise cuts, but they’ll punish sloppy technique.

Santoku vs deba/yanagiba/sakimaru: deba is for fish breakdown, yanagiba/sakimaru for sashimi pulls; santoku isn’t a replacement for single-purpose geometry.

Also, santoku knives are often compared to the chef’s knife, with clear differences in design and technique. Santoku’s flatter edge rewards push-cuts and straight-down chopping more than big rocking motions.

Can a santoku cut meat well?

Yes—within its lane. A santoku knife is built to cut meat, especially boneless proteins, because the santoku knife is designed for slicing, dicing, and chopping a variety of ingredients, including vegetables, fish, and boneless meats.

It handles chicken breast strips, pork for stir-fries, and beef for stews without drama. Santoku knives excel in preparing dishes like slicing fish for sushi, chopping vegetables for stir-fries, and cutting meats for stews—board work all day, clean cuts all the way.

What it should not do is brute work. Due to harder and more brittle steel, santoku knives should not be used for cutting through large bones or frozen foods. That’s deba territory, or a cleaver designed for it.

What mistakes ruin santoku edges?

Most edge damage isn’t from sharpening mistakes—it’s from daily habits. Rule one: use a wooden or plastic cutting board to maintain the blade’s edge. Glass and stone boards will chew up sharpness fast.

Rule two: avoid putting a santoku knife in the dishwasher. Heat, impact, and harsh detergent are where good knives go to die, and they don’t even get a respectful funeral.

Rule three: match the knife to the task. When someone chips a santoku, it’s often from twisting in hard food, prying, or levering around a bone—not from “bad steel.”

How does proper care look day-to-day?

Care is simple, but it has to be consistent. Always hand wash the santoku knife with mild soap and warm water to prevent rust or corrosion. A neutral detergent is fine—no need for anything fancy, just not the “strip paint” stuff.

Then dry the santoku knife immediately after you wash it to prevent rust. That one habit solves most mystery spots, especially on carbon steel.

Two more small moves help: wash the santoku knife right after use (acidic juices don’t pause the clock), and store it in a knife block, sheath, or magnetic strip so the edge doesn’t smack into other tools. For cleaning, a soft sponge is the safe default—skip abrasives that can scratch finishes and creep toward the edge.

How often should sharpening happen?

A santoku stays fun when the edge is maintained lightly and often, not “rescued” once a year. Sharpen the santoku knife regularly with a whetstone or honing rod to maintain sharpness and edge retention.

With carbon steel, that regular touch-up is part of why pros like it: long-lasting sharpness after a single sharpening can mean fewer full sessions on stones.

In a forge setting (MG Forge included), a simple finishing check is whether the edge glides through paper without snagging and still bites into tomato skin. After that, the rest is maintenance and not mistreating your cutting board.

What helps prevent rust on carbon steel?

Carbon steel is honest: it reacts to water and acids, and it will show it. One classic step is also the simplest—apply a light coat of vegetable oil to help prevent rust.

This matters most if the knife will sit unused for a week or the kitchen is humid. Patina is normal and often protective; orange rust is not the vibe.

If you’re storing a carbon steel santoku for longer, keep it clean, dry, and lightly oiled. The goal is to prevent rust, not to babysit it—just don’t leave it wet on the cutting board like it’s a spoon.

Which santoku should be chosen in 2026?

Trends have shifted toward “fit your life” instead of chasing one magic steel. Santoku is showing up in more deliberate builds too: thinner grinds for vegetable-heavy cooks, and slightly thicker 2.5–3 mm spines for people who want confidence over ultimate slicing feel.

A simple checklist stays practical:

Blade length: around 170 mm is the baseline; adjust if board space is tight.

Thickness: 2–3 mm for home use is a safe range.

Steel: choose stainless steel for low-stress ownership, carbon steel for peak bite and sharpening feel.

Weight/handle: aim for 120–200 g and a secure grip; handle shape affects control and safety.

If the santoku knife has a Granton edge, expect smoother release on sticky foods—but don’t treat it as a replacement for good technique, a sane cutting board, and not forcing the tip through hard produce.

What is the difference between a santoku and chef knife?

A santoku usually has a shorter blade (often around 170 mm) and a flatter edge that favors push-cuts and straight-down chopping. A chef’s knife (gyuto style) more often runs 210/240 mm and supports longer slicing strokes. They overlap, but the santoku tends to feel more compact and controlled on small boards.

What is the best brand of santoku knife?

There isn’t one universal “best,” because steel type, grind, and balance matter more than a logo. For budget-friendly options, Tojiro santoku knives are praised for their nimble, sharp blades and compact handles, often cited as a solid choice under $100. In general recommendations, the Mac Hollow Edge Santoku Knife is highly recommended for easy slicing across many ingredients.

What knife does Gordon Ramsay prefer?

Public mentions and media clips often show him using a Western-style chef knife profile for broad prep tasks. That choice fits his fast, high-volume style where longer blades and rocking cuts are common. Specific models can vary by setting, so it’s safer to focus on the profile rather than one exact knife.

Do professional chefs use santoku?

Yes, especially for vegetable-heavy prep and compact workstations. Many professional chefs like santoku in carbon steel because it can take an extremely sharp edge and hold it well after you sharpen it. In specialized stations (sushi, fish breakdown), a chef may switch to yanagiba, sakimaru, or deba for the job-specific blade shape and precision.

How does santoku design affect control, sticking, and edge retention in everyday prep?

A santoku is often treated as an essential japanese kitchen knife because its shape, length, and tip promote control across common cutting styles, from cutting vegetables to portioning meat and fish, while staying suitable for tight boards and fast cooking; compared with gyuto or nakiri, its flatter profile supports precise cuts and efficient movement through food, and its wide blade helps protect knuckles and improves transfer, with some finishes reducing sticking. Choosing steel and stainless options is mainly about maintenance and edge retention, while materials, handle geometry, and craftsmanship (including builds like MG Forge) influence balance and how confidently the edge tracks; a thick blade can feel more durable, but a thinner grind can still be suited to delicate work, and the right stock behind the edge matters as much as spine thickness. For care, knives are prone to damage when misused on hard surfaces or for prying, so gentle technique and consistent habits—especially hand clean, quick dry, and proper wash routines—help preserve performance and keep prep smooth across dishes.