Tamahagane steel knife: worth it & how it performs

Is a tamahagane steel knife “worth it”?

Yes—if what you want is a piece of living Japanese blade culture, not a materials-science cage match with modern alloys. A tamahagane steel knife can cut beautifully, take a crisp edge, and show an almost organic surface character in the hand. If the romance is part of the brief, you’re in the right aisle.

Here’s the catch: tamahagane knives are often seen as behind modern carbon steels on pure, repeatable performance, even though they’re prized for history and craftsmanship. That gap between vibes and metrics is where most buyer’s regret lives in 2026—especially if you expected “legendary steel” to behave like a maintenance-free laser.

In practice, treat Tamahagane as a heritage material choice. It’s closer to choosing a single-bevel yanagiba for sashimi—specialized, intentional, and a little demanding—than grabbing a stainless chef knife and forgetting it exists.

What exactly is tamahagane steel?

Tamahagane steel is traditional Japanese steel made from iron sand and charcoal in a tatara steel setup (a tatara furnace). It’s the material historically associated with Japanese swords, so yes, the name carries weight in kitchen knife circles for a reason.

The word Tamahagane is often translated as “jewel steel” and sometimes “precious steel,” because making it well is skilled, slow work. And unlike many modern carbon steels, Tamahagane is relatively “simple” in composition—no intentional dosing of elements like manganese and silicon to force consistency.

That simplicity has a real outcome: variation. The carbon content typically falls around 0.5% to 0.8%, meaning varying carbon content across pieces can affect hardness, feel on stones, and edge retention. Two billets can share a name and still behave like two different moods.

How does tatara smelting shape the steel?

Tamahagane is produced through a traditional smelting process: iron sand and charcoal are fed into a tatara furnace, and the work is labor-heavy by design. The smelt runs about 72 hours, with continuous feeding, so the material becomes “expensive” before a forge even heats up.

Inside the tatara, layers of charcoal and iron sand do their job, with charcoal acting as the reducing agent that turns magnetite toward iron. Traditional production can yield low levels of harmful impurities like phosphorus and sulfur, which is one reason Japanese blade making trusted it for blades expected to survive real use.

After smelting, the tamahagane production process includes sorting by grade, which roughly tracks carbon level. That step matters: a smith can pick harder pieces for the cutting edge and tougher material for support, instead of forcing one uniform bar to be everything at once.

What does folding really change?

Traditional forging involves repeated folding and hammering to refine the material, create very fine structure, and help drive out slag. This is also where the “alive” look comes from: Tamahagane can show a distinctive grain tied to smelting, refinement, and the way the blade is worked at the forge.

One formal name for this is Orikaeshi-tanren: repeated hammer-forging and folding intended to improve purity, uniformity, and toughness. It’s worth saying out loud—folding isn’t a cheat code; it can tidy up consistency and manage inclusions, but it doesn’t automatically outperform a well-made modern steel.

And yes, it varies. Inclusion content can differ from batch to batch, with some studies reporting values as high as 1.9% in ancient swords. In a workshop, that’s why a careful smith forges, normalizes, then watches how the steel “talks back” during grinding before committing to a thin final geometry.

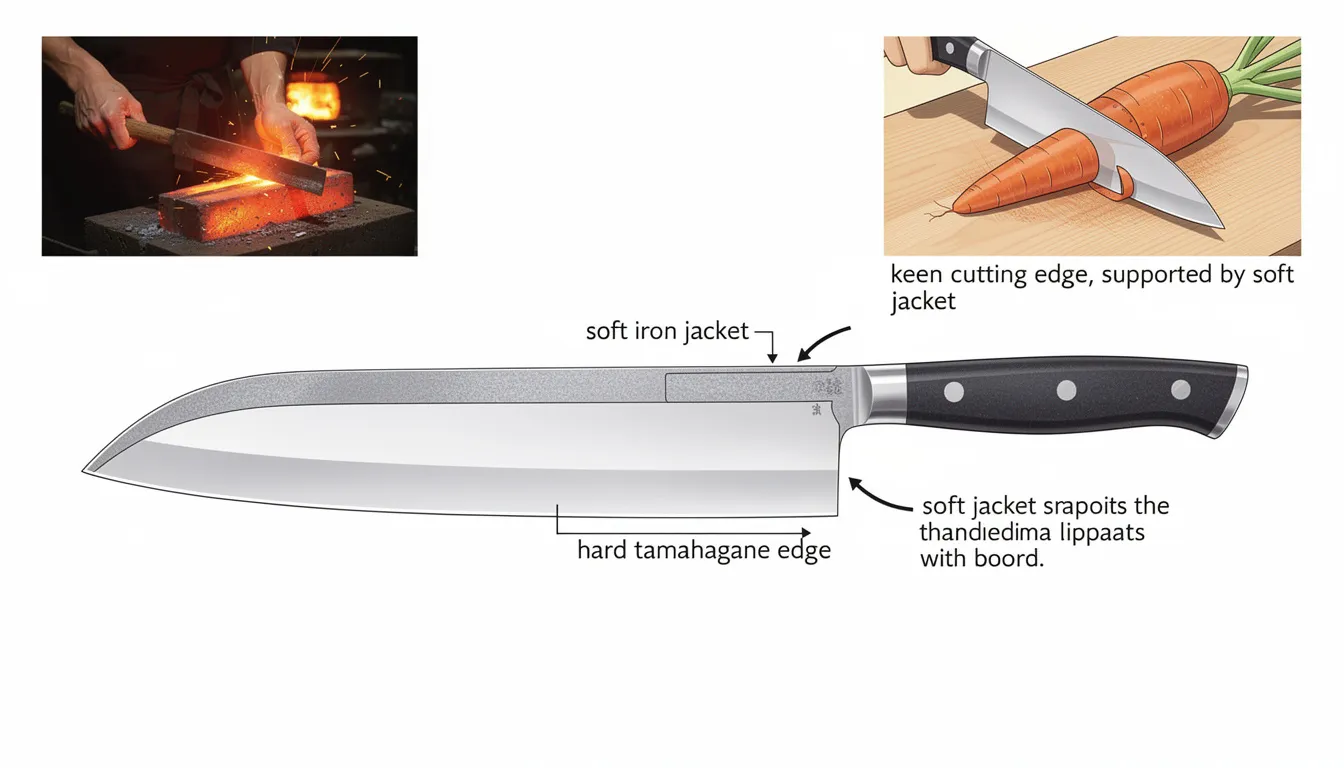

Why is lamination common with Tamahagane?

Tamahagane is often used in laminated construction because hard steel is supported by softer iron or mild steel. That hard-edge/soft-jacket approach helps the blade take a keen cutting edge without feeling like a brittle shard when it meets a board edge or a dense carrot root.

In kitchen terms, lamination supports thin work. A 210 mm gyuto can be ground to a fine, push-cut-friendly edge while the softer cladding helps absorb shock. A single-bevel yanagiba at 270–300 mm benefits even more, because long bevels demand stability along the whole blade face.

At MG Forge, this is where geometry stops being theoretical. A small change in spine thickness—say, from about 3.0 mm near the heel to 2.4 mm—can decide whether the knife feels like a laser slicer or a chippy diva, especially with high-carbon edge material.

Which knife styles fit tamahagane best?

Some profiles simply play nicer with what Tamahagane wants to be. Because tamahagane knives are handcrafted, variation in weight and dimensions is normal, so picking a forgiving format can save you pain later.

A practical match-up tends to look like this:

Yanagiba / sakimaru (270–330 mm): best for sashimi and clean protein slicing; single bevel rewards careful sharpening.

Gyuto (210/240 mm): the most “normal” daily driver; double bevel is easier to live with for mixed prep.

Bunka or kiritsuke (180–210 mm): great for vegetables and clean tip work; keep the edge angle conservative if the grind is very thin.

Petty (120–150 mm): small tasks, citrus, trimming; less board impact means fewer surprises.

Deba: works, but heavy fish butchery adds impact; lamination and thicker edges matter more here.

If a western chef knife pattern is your comfort zone, Tamahagane can still work—just expect a more reactive surface and a bit more structure behind the edge than the thinnest Japanese lasers. And if you’re the type who likes tradition in pocket form, the kogatana knife is a classic point of reference in Japanese blade making.

How good is edge retention, really?

Tamahagane is known for high carbon potential, which can translate to impressive sharpness and edge retention when the edge is well supported. That 0.5%–0.8% carbon range helps explain why a fresh edge can feel “sticky” on tomato skin or sashimi fibers, especially at a thin, well-ground cutting edge.

But people are often surprised that tamahagane knives don’t always justify their price versus modern carbon steels on pure performance. That’s not an insult to Tamahagane—modern metallurgy is consistent, and consistency is a form of performance you notice every day.

A shop-floor micro-case makes it real. Two blades forged to the same 210 mm gyuto pattern can sharpen differently: one deburrs clean and keeps a crisp bite through a full prep shift, the other feels slightly crumbly at very low angles. That’s the reality of a material whose inclusions and carbon zones can vary from piece to piece.

What about Damascus, wrought iron, and finishes?

Tamahagane knives are often loved for aesthetics—surface character, contrast, and the way finishes make the blade feel like a tool instead of a museum piece. Wrought (fibrous) iron can add a soft wood-grain look; forge-welded Damascus can add movement; and a scuffed kasumi finish can make the whole blade read more honest than flashy.

It’s worth separating terms, because 2026 marketing gets sloppy fast. “Damascus” can mean real forge-welded layers or a patterned stainless cladding over a different core; in use, what matters is still the edge steel, the grind, and how the cutting edge is supported.

If a knife is sold as Tamahagane (or under a tamahagane brand label), the most honest value shows up in the builder’s choices: core placement, bevel symmetry, and whether the finish supports maintenance. Mirror looks incredible, but it also makes scratches and fingerprints louder—especially on reactive steel.

How much maintenance does Tamahagane need?

Tamahagane needs real maintenance to protect against rust and staining, compared to stainless steels that shrug off abuse. In a busy kitchen, the difference is habits, not rituals: do the basics, and life is easy; ignore them, and your blade will complain in orange freckles.

To prevent rust on Tamahagane steel knives, wash with clean hot water after use and dry thoroughly. That simple routine stops most issues, including the “it sat damp for 20 minutes by the sink” corrosion surprise.

It’s also recommended to store Tamahagane steel knives in newspaper if the knife will sit unused for weeks. Patina isn’t failure: a stable grey-blue patina is often the steel settling in, not breaking down.

How should a Tamahagane edge be sharpened?

Using stones is essential for keeping Tamahagane happy. A no-drama setup is a medium stone around 800–1200 grit for maintenance, then 3000–6000 for refinement, depending on whether you want a polished protein edge or a little bite for vegetables; either way, you’re chasing the right edge, not a number.

To sharpen Tamahagane steel knives, the usual advice is to keep the flat factory bevel and avoid adding a micro-bevel. On some modern steels, micro-bevels are a safety blanket; on some Tamahagane edges, they can change how the cutting edge bites and how cleanly it deburrs.

Deburring should be done with very light finger pressure. This is where people wreck edges: too much force flips the burr back and forth until the edge fatigues, and then the knife feels “sharp but weak” on the first onion.

If you’re sharpening a single-bevel yanagiba, keeping the wide bevel flat on the stone is the whole game. A little rocking might seem harmless, but it can create low spots that show up as steering in long sashimi pulls.

Where does the tradition show up today?

Tamahagane has a long history as a preferred material in Japanese blade making, tightly linked to japanese swords and the broader sword tradition. The craftsmanship behind Tamahagane knives is rooted in lineages that stayed alive through repetition: the same tools, the same techniques, the same lessons paid for in time.

Some lineages are tied to specific places and names, like Shirou Kunimitsu, a historic blacksmith forge in Omuta, Fukuoka, with a legacy spanning over two centuries. The forge draws foundational ideals from Miike Denta, a celebrated swordsmith of the Heian period—one of those line stories that reminds you this isn’t just “steel,” it’s a culture that kept receipts.

Most tamahagane produced in Japan comes from Nittoho tatara in Shimane Prefecture, the last of its kind. That bottleneck is one reason the material stays rare, why japanese swords (including katana) still dominate the reference points, and why the phrase “real Tamahagane” remains a conversation, not a commodity category.

A modern maker’s job—MG Forge included—is to treat that tradition as responsibility, not cosplay. That means testing geometry, being honest about maintenance, and building a tamahagane steel knife that works on a cutting board, not only in a display case.

What is special about Tamahagane?

Tamahagane is traditional Japanese jewel steel smelted from iron sand and charcoal in a tatara furnace, historically tied to japanese swords and swordmaking. It’s refined through repeated forging and folding to improve purity and structure, and it can show visible layers and surface character that many people associate with classic japanese blade making. In kitchen knives, it’s valued as much for heritage and craftsmanship as for measurable performance.

Why is Tamahagane so expensive?

Tamahagane is expensive because production is labor-intensive and skill-heavy, including a tatara process that runs for about 72 hours. After smelting, the steel is sorted by grade, and the knife itself is typically handcrafted, which adds time and variability—especially with carbon steels that can differ from piece to piece. The cost often reflects traditional methods, scarcity in Japan, and the work needed to refine and forge the material more than guaranteed performance gains compared with modern carbon steels like white steel.

How do traditional methods and material variability shape the characteristics and sale value of tamahagane kitchen knives?

In kitchen knives, tamahagane brand pieces made from tatara steel are often framed as precious steel because traditional methods in a furnace produce high quality steel with visible layers and distinctive characteristics, but also a small amount of variation in elements that can be hard to measure with perfect precision, so carbon steels like this can be compared with white steel in terms of consistency, high hardness, and how refined the edge feels; that same variability affects production class sorting and workshop decisions (line geometry, support from lamination, and stock selection), and it also raises practical concerns like cracking risk if the form gets too thin, plus ongoing needs to protect reactive surfaces after use—factors that shape what’s suggested in videos and at point of sale, and even how different languages describe the material, as makers such as MG Forge note and pay attention to during crafted finishing and final tuning (produce; material; compared; create; crafted; refined; note; suggests; support; protect; sale; class; stock; form; line; precision; elements; measure; cracking; production; furnace; high hardness; visible layers; traditional methods; small amount; characteristics; languages; videos; pay).