Japanese fish knife: types, uses, and key geometry

What is a japanese fish knife?

A japanese fish knife is a purpose-built tool for clean fish prep: breaking down, fish filleting, portioning, and slicing with minimal drag. Unlike a general japanese knife like a gyuto, these knives are often tuned around one stage of the process—head-off work, skinning, or sashimi cuts. High-quality Japanese fish knives can feel almost “guided,” because the geometry is built for control and low friction. In practice, that means fewer torn fibers and less of that paste-like sheen on the fish surface.

A big part of that “guided” feeling comes from how thin and light many Japanese blade profiles can be. The lightweight build favors precision and calm cuts over brute force, even when you’re filleting fish and the board is already wet. That’s why a smart fish kit often pairs one sturdy tool for breakdown with a long, narrow slicer for finishing. The details matter: a 150–180 mm workhorse for whole fish work, then 240–330 mm for clean slicing.

There’s also a very 2026 reality: buyers now want the “why,” not just “is it sharp.” People ask about edge angles and heat treatment because fish is where those choices show up instantly. Yes, a sharp knife helps, but geometry is the quiet part that makes the cuts look effortless.

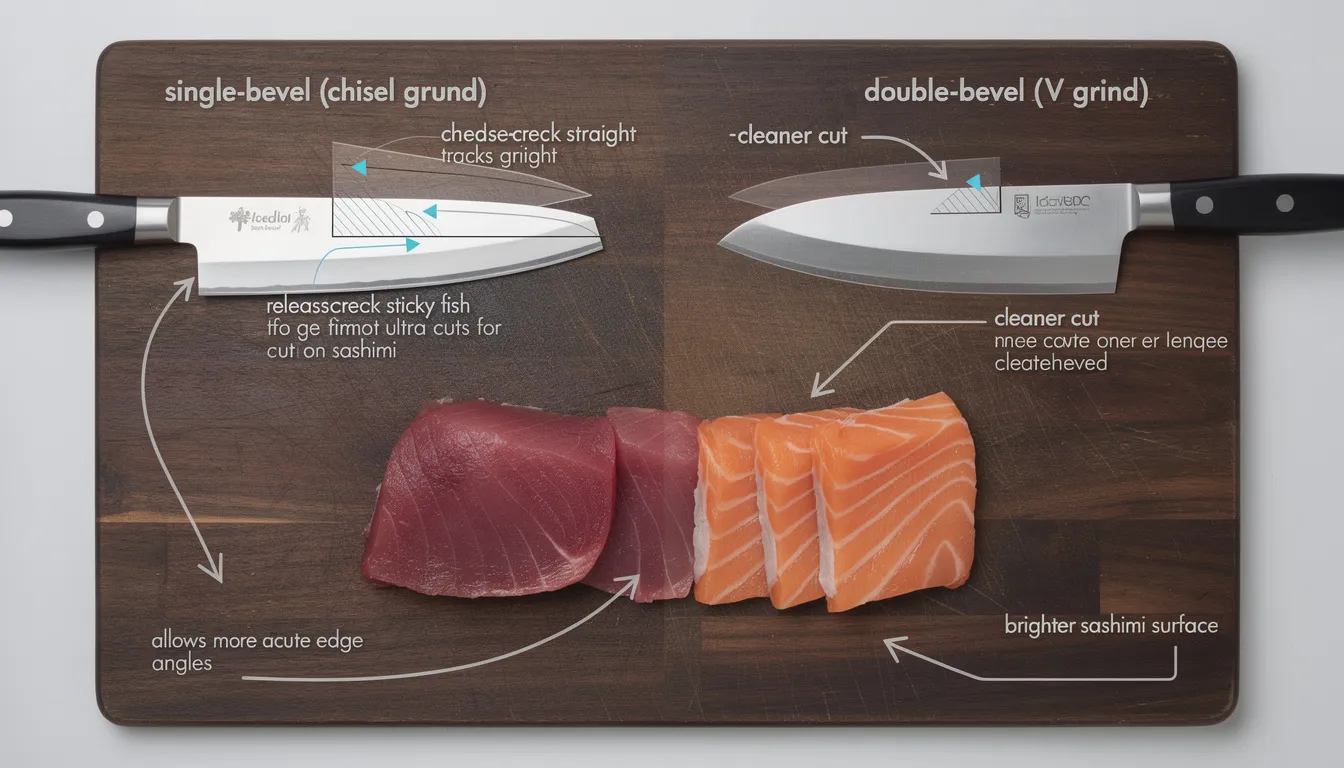

Why does single bevel matter?

Many Japanese fish knives are single-beveled (chisel-ground), while Western knives are typically double-beveled (V-shaped). That one decision changes how the blade tracks, how it releases sticky food, and what kind of sharpness it can actually hold. Single bevel geometry can run more acute edge angles, which helps produce cleaner cuts that reduce oxidation and tearing in delicate flesh. The result is often a brighter, smoother surface on sashimi.

Edge angle is the concrete difference you can feel. Japanese knives commonly run around 15–16°, while many Western knives sit closer to 20–25°. Narrower angles create a razor sharp edge, but they also demand better technique and a calmer board. With fish, the payoff is immediate—especially on skin or translucent slices where ragged edges announce themselves.

Single-bevel edges also include a concave backside that reduces friction. That hollowed back helps the blade glide and release instead of sticking and dragging. In the shop, it’s one of those features that looks subtle until you sharpen it and suddenly understand why the knife “wants” to go straight.

Which knife for which fish job?

Japanese fish knives are specialized tools, and that specialization is the whole point. For breaking down whole fish, the conversation usually starts with the deba knife (or simply, deba). For sashimi slicing, it shifts toward a yanagiba and its variations. A Western-style filleting knife can be excellent too, but it’s a different approach to blade shape, flex, and control.

Here’s the simple map that tends to work in real kitchens:

Deba knife (150–180 mm): head, fins, collars, and working through small bones

Yanagiba (240–330 mm): skin removal and sashimi slices with long pull strokes

Petty (120–150 mm): trimming, pin bones, and tight detail work

Western style chef knife (210–240 mm): general prep when fish is only part of the menu

A common mismatch is using flexible fillet knives for jobs that quietly require a thick spine. Flexible blades shine when you’re riding rib cages on softer fish during filleting, but they don’t love clipping fins or nudging through joints. That’s why Japanese kits often split “breakdown” and “slicing” into two tools with different shapes.

Also worth saying out loud: a super sharp edge isn’t automatically the right edge for every moment. Fish prep asks for stiffness in one cut and glide in the next, and the right blade shape makes “super sharp” feel calm instead of twitchy.

What makes a deba knife different?

The Deba knife is built for breaking down whole fish and cracking through small bones without drama. It’s thick at the spine and usually single-beveled, so it can make precise, strong cuts into fish and other meat. Deba knives are designed to deal with small bones and fins—work that would feel risky with a thin blade slicer. In a sushi kitchen, that’s why the deba is traditionally used for deboning and filleting fish before it becomes sushi or sashimi.

There’s history baked into the shape. The Deba originated from the Saiko region of Japan during the Edo era in the middle of the 19th century. The word “Deba” translates to “pointed carving knife,” which matches the profile and purpose. It’s also one of the oldest Japanese knives still in use, and that’s usually a hint the design survived a lot of hard days.

Practically speaking, a versatile deba often lands at 150 to 180 millimeters (roughly six to seven inches). That size gives enough heft for stability while still feeling nimble on a board. When choosing a deba, experience level and fish size matter, because the knife will happily punish sloppy twisting near bones.

How does yanagiba slicing really work?

The Yanagiba is a long, slender knife used for gently removing fish skin and slicing fish into sashimi. It’s a single-beveled knife, meaning it is sharpened on only one side. That single bevel, plus the long narrow profile, is why it’s particularly suited for fresh sashimi: one clean pull cut can finish a slice with minimal sawing. In sashimi work, fewer strokes usually means less surface damage.

Geometry drives the technique. Longer blades—often 270 mm and up—encourage a single, continuous draw for slicing. Shorter slicers can work, but they invite extra strokes, and extra strokes show up as haze on glossy fish. This is also where a super sharp edge is not a flex but a requirement, because the blade should separate fibers without compressing them.

There are specialized variations too. The Takobiki is used for slicing octopus, and the Fuguhiki is an ultra-thin version of the Yanagiba designed specifically for paper-thin slicing of fugu. Both repeat the same lesson: Japanese tools don’t try to be universal; they try to be extremely good at one job.

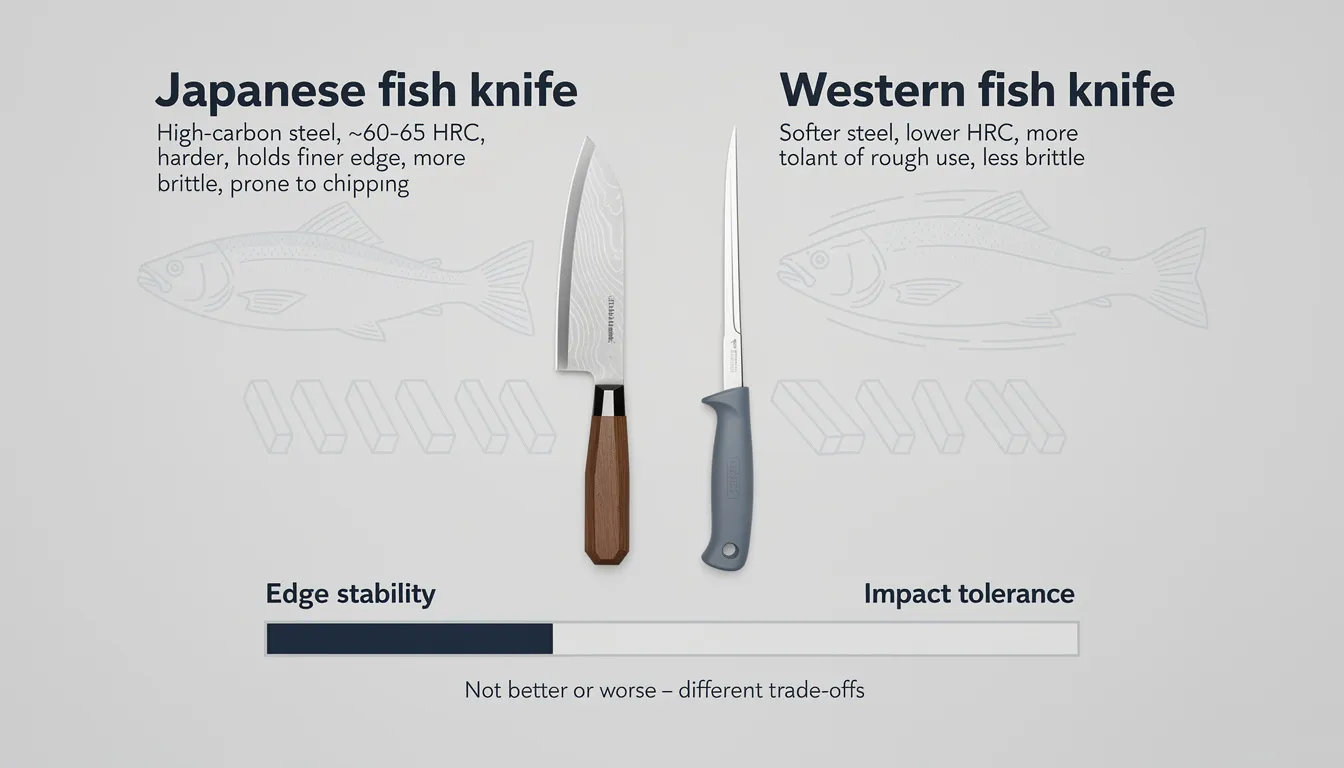

What about steel and hardness?

Many Japanese fish knives are forged from high-carbon steel and often sit around 60–65 HRC, which helps them hold an edge longer but also makes them more brittle and prone to chipping than softer Western steel. Harder Japanese steel tends to keep a fine edge, while Western steel is usually softer and more tolerant of rough use. That isn’t “better vs worse,” it’s a trade: edge stability versus impact tolerance. Fish prep rewards edge stability because the cutting is controlled and repetitive.

This is also where carbon steel becomes the main character. Traditional debas may be made with carbon steel, which needs regular oiling to prevent rust. In return, carbon steel can take a very crisp edge and feel predictable on stones. Some cooks love that feedback; others want lower maintenance and fewer rituals between services.

Modern stainless steel debas don’t require the same care as carbon steel. In 2026, stainless metallurgy is good enough that many chefs choose stainless for volume work and reserve carbon for personal knives and slower sharpening sessions. Either way, you’re matching steel behavior to kitchen reality, not to a spec sheet.

In the forge, this trade shows up during heat treatment choices. A deliberately hard, sharpened edge can sing on a stone and bite into fish skin with almost no pressure. But the same hardness will chip if the blade is twisted into a joint like it’s a pry bar, which it definitely is not.

How does filleting fish with a deba go?

Filleting fish with a Deba knife typically starts with removing the head and gutting the fish before slicing. A deba’s mass and thick spine help guide controlled cuts through collars and around fins. The goal isn’t speed; it’s clean separation along natural seams. That’s why many chefs describe the deba as a “breakdown” knife rather than a thin slicer.

A sturdy grip is essential, because fish can be slippery and, yes, sometimes bloody. Handle shape and finish matter more here than in vegetable prep because moisture and oils show up fast. A good deba should have a handle that won’t become slippery when wet—especially during the first minutes of breakdown when the board is a mess.

Fish bones change how you use the knife. A deba is designed to cut through small bones, but “small” still means technique matters: short, controlled pushes and careful alignment. Hitting bones straight on is different from twisting into them, and twisting is where chips happen on hard steel.

In the workshop, one common fix is not more sharpening—it’s assigning the knife a better job. If someone insists on one blade for everything, a gyuto plus a small petty often covers most home fish breakdown more safely than forcing a deba into delicate slicing. MG Forge ends up repeating that advice because it saves edges and saves nerves.

How is size chosen?

Blade length guidelines are simple, but they matter. A 150–180 mm deba covers most home fish—think sea bream-sized work—without feeling like a cleaver. Bigger fish and heavier collars can justify longer, heavier blades, but that’s usually a second purchase. For slicers like yanagiba, lengths around 270–300 mm are common because they support single-stroke sashimi slicing.

Hand size matters too. Choosing a deba that fits your hand improves dexterity and control, especially when you’re working close to the board during filleting and trimming. If the handle is too large, grip tension rises; too small, and the blade feels unstable. Both problems show up as messy cuts near the spine and rib line.

There’s also the “what fish do you actually cook” rule. When species and size change weekly, it’s safer to pick a moderate deba and add a longer slicer later. When the menu is stable—say, daily salmon breakdown—a more specialized size can make sense. In 2026, that kind of intentional kit-building beats buying one expensive blade and hoping it becomes a miracle.

How is a deba maintained?

Deba knives reward basic, boring habits that prevent most damage. The essentials: hand wash, dry fully, and store so the edge can’t knock into other tools. Putting a deba in a wooden block (or any storage that protects the blade) is a small habit that saves a lot of edge repair later.

Sharpening is the other pillar. Use a whetstone to sharpen the deba when it stops cutting as cleanly as you want. Single bevel sharpening also means treating the flat side and bevel side differently, because the geometry is the performance. It’s less about chasing a mirror finish and more about keeping the blade tracking straight and feeling stable.

Carbon adds one more step. Very traditional carbon steel debas need regular oiling to prevent rust, especially if they sit for days between uses. A light camellia oil wipe is common, but even neutral food-safe oils work if applied thinly. Patina is normal; red rust is the problem, and it’s usually avoidable.

A small workshop note from MG Forge: most “mystery chips” we see aren’t from bad steel, but from storage collisions or board contact with bone at a bad angle. The fix is typically calmer technique and safer storage, not chasing harder heat treatment or blaming the knife.

Where do flexible fillet knives fit?

Flexible fillet knives exist for a reason: when the job is riding along bones and making sweeping, low-resistance passes on softer fish. They’re usually double-beveled, so they feel familiar to most cooks right away. But they are not the same thing as a deba, and pretending they are is how people end up frustrated. Deba knives are different from flexible fillet knives because they’re designed for stiffness, durability, and working through fins and small bones.

This is also where people mix up a filleting knife with a boning knife. A boning knife is typically built for meat connective work and joint navigation—think chicken and bigger cuts—rather than sashimi-quality surfaces. A deba, by contrast, is a traditional Japanese work knife for fish prep, built to stay stable under pressure with a thick spine and controlled cutting.

Steel behavior ties back in here. Harder edges can be super sharp and hold that feeling longer, but they don’t like lateral stress. Flexible blades tolerate bending and flex, but they usually won’t feel as glassy when slicing sashimi. Matching the knife to the moment—breakdown versus slicing—solves most problems before they happen.

If research feels like a lot, videos help because technique is visible. Watching how chefs use a deba on whole fish makes the design logic obvious in about thirty seconds.

How are materials and finishes understood in 2026?

In 2026, there’s more interest in what a blade actually is, not just how it photographs. Terms like Tamahagane, fibrous iron cladding, and forge-welded damascus come up constantly in Japanese knife conversations. Those choices can influence sharpening feel, corrosion behavior, and how smoothly a blade moves through food. But it’s also true that patterns can be mostly aesthetic, depending on construction and grind.

A practical rule still holds: geometry usually beats pattern. A well-ground single bevel with a correct concave back will outcut a flashy blade with sloppy angles, even if the flashy one costs more money. Another rule: harder steel can improve edge retention, but it demands better habits—calm cutting, softer boards, and storage that doesn’t let knives break each other in a drawer.

From the forge side, the interesting trend is transparency. Makers are more open about heat treatment targets, grind style, and intended use, which helps buyers choose between a deba for bone work and a slicer for sashimi without guessing through marketing. MG Forge’s approach is similar: control the steel, tune the grind, and let the knife behave predictably when fish gets slick.

If you came here looking for a japanese fish knife as a single “do it all,” the honest answer is: pick the tool that matches the task. Break down with deba, finish with a slicer, and your cutting gets cleaner without needing hero-level sharpness tricks.

How do blade geometry and handling affect fish filleting results?

Successful fish filleting depends on a knife that has enough heft for breakdown work and stable tracking, especially when the surface gets slick, paired with geometry that minimizes drag for clean slices. Harder Japanese steels can improve edge retention, but they require calm technique and correct angles to avoid damage during bone-adjacent cuts. Good habits—washed, dried, and wiped storage—prevent the kind of incidental edge knocks that workshops like MG Forge often see, and reduce the risk of chips from (art)ificial drawer collisions.