Western style chef knife: what makes it dependable

What makes a western style chef knife special?

A western style chef knife is the kitchen workhorse for slicing, dicing, chopping, and mincing. In 2026, that job description is the same—but people are sharper about why it feels so dependable. Compared to many Japanese blades, it’s usually thicker at the spine, often heavier, and built to tolerate daily board contact without turning it into a drama series about microchips and regret.

Most western style knives also share a very user-friendly promise: predictability. They’re typically easy to control and maneuver, even though they’re bulkier than a small utility knife or paring knife. That stable feel comes from familiar proportions, a consistent grind, and an edge angle that doesn’t feel twitchy in average home hands.

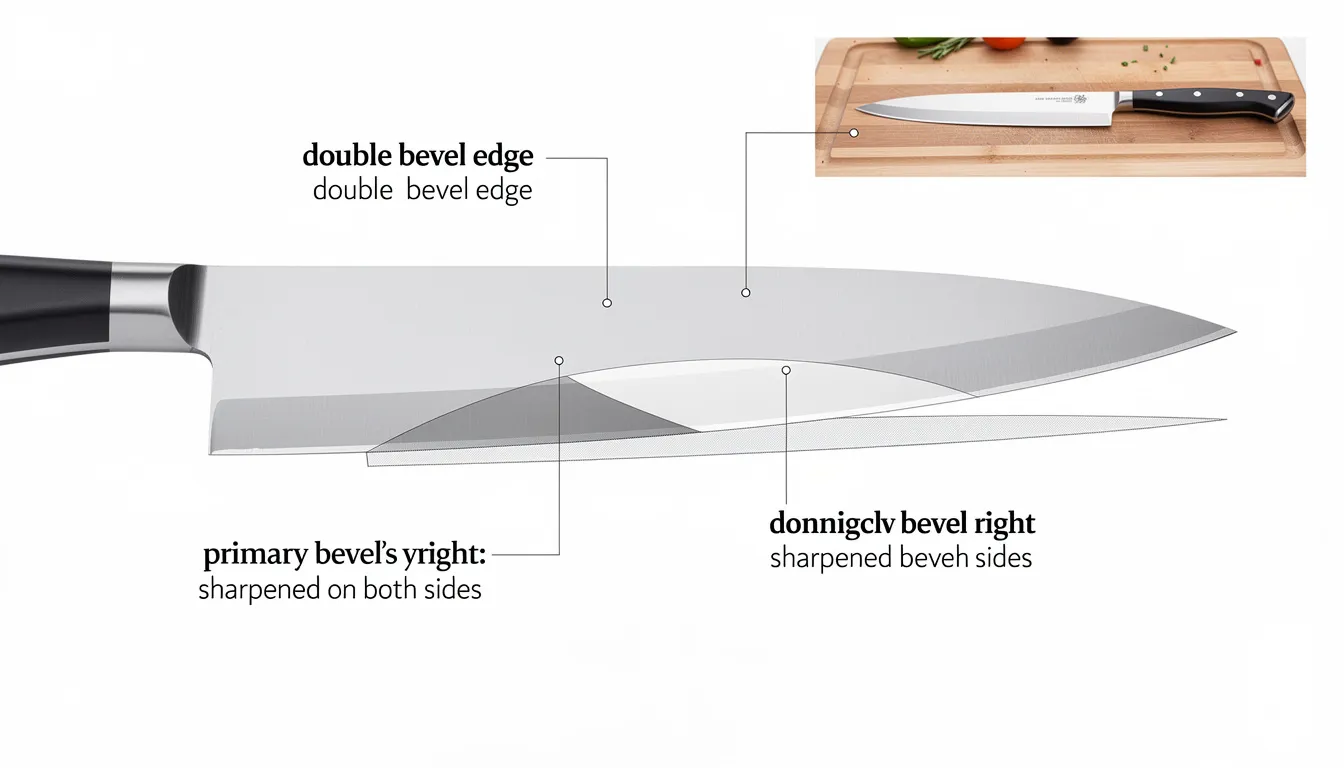

What edge geometry shows up most often?

Western-style knives are typically ground with a double bevel edge, sharpened on both sides of the blade. In real use, that means a symmetrical, intuitive feel: right-handed and left-handed cooks can grab the knife and get to work without “learning the tool” first. Most western knives today use a balanced, V-shaped bevel that’s become the classic baseline for european knives and their descendants.

That classic V is also why this style knife is so forgiving. If the blade edge rolls a bit with daily use, you can often realign it quickly on a honing rod. And because the geometry isn’t extreme, it usually tracks straight through dense foods like Daikon or Kabocha without demanding perfect techniques from the user.

How does the blade shape change the cutting motion?

The blade profile on western style knives is typically more curved, which naturally supports a rocking motion while cutting. That curve isn’t just a “Western look”—it changes fatigue. A blade that’s too aggressively curved forces extra lifting over the food during chopping, and that effort adds up fast over a long prep session.

A curved profile also pairs well with an 8-inch (about 210 mm) do-most-things length. There’s enough belly for rocking herbs, yet enough flat to push-cut onions if the edge isn’t overly rounded. It’s a small decision in blade shape with big consequences in real-life kitchen rhythm.

What steel feels “right” in use?

Blade material is personal preference: stainless steel is more forgiving, but it can go dull sooner than carbon steel. Most western style knives use high-carbon stainless steel—still a high carbon steel approach in spirit, but generally softer and less likely to chip than many Japanese high carbon steel options. That “forgiveness” is a big reason a western style chef knife stays ideal for home cooks, especially beginners.

Western chef knives are commonly built with softer steel (around 54–58 HRC), making them less prone to chipping. For home cooks, a frequently mentioned sweet spot is roughly 57–60 HRC, balancing bite and toughness—though many classic Western profiles sit a bit lower. Softer steel trades some edge life for durable behavior and easier sharpening at home.

How do Japanese steels fit into this conversation?

Japanese knives are often made from high-carbon steel, which can take a sharper edge but may chip more easily. Japanese-style knives also commonly include specialist single-bevel tools, sharpened on one side—especially slicer styles like yanagiba or workhorses like deba for fish. They’re often lighter, with a thinner blade that rewards precision and clean cutting.

On the grinder, the difference is obvious. A thin Japanese-style gyuto at 210 mm can feel fast and clean through fish or ripe tomatoes, while a sturdier western style chef knife is happier living in the messy middle of cooking: harder squash, quick board work, and small collisions with imperfect habits. Tight tolerances are wonderful—right up until they punish you for being human.

What do weight and balance actually change?

Weight matters when choosing a chef knife: some cooks like a heavier blade for cutting power, others want something lighter for precision. Western style knives are generally heavier with thicker blades than many Japanese-style options, and the thicker stock plus full-tang construction adds real heft for heavier tasks.

But weight only helps when balance is right. Many western style knives include a bolster that protects fingers and contributes to that familiar centered feel. A good chef knife should be easy to maneuver: you should be able to place the tip accurately even when the blade is built more like a tool than a scalpel.

What handle details matter most?

Western “Yo” handles are often riveted wood or composite, built for ergonomic comfort and secure hold. That matters on long prep days, because comfort beats aesthetics when you’re 40 onions deep. A handle that fills the palm well can make an 8-inch knife feel smaller, and a slick handle can make even a 180 mm blade feel like a bad idea.

There’s also a quiet advantage to the common Western setup: repeatability. With a predictable handle and bolster, many cooks can switch between a chef knife and a boning knife without recalibrating grip and wrist position. When your pace increases, familiar structure reduces mistakes.

How does this compare to “Eastern” chef knives?

Western knives and Japanese knives often diverge in edge style and cutting style. Western style knives usually run a double bevel and a more curved profile, while many Japanese chef knife patterns lean straighter for push-cutting and clean slicing. Specialist Japanese blades often go single-bevel, especially for fish and dedicated slicer work.

Steel choice shifts behavior, too. Western style knives are commonly made from softer stainless steel, which is easier to maintain and less likely to chip. Japanese knives often chase maximum sharpness with harder steel and thinner grinds; that bite is impressive, but twisting in dense vegetables or using hard surfaces can make things break in ways nobody enjoys.

When does a western style knife win in the kitchen?

When speed, robustness, and mixed tasks matter, western style knives earn their reputation for precision and versatility. They’re made for the full mess of dinner prep: slicing, dicing, chopping, mincing—then doing it again tomorrow. And because the geometry is symmetrical, the knife is suitable for both right-handed and left-handed users without special ordering or compromise.

This is why many cooks keep a western style chef knife even after falling hard for Japanese profiles like santoku or nakiri. A western style chef knife doesn’t demand perfect angles, perfect board contact, or perfect restraint. It just asks for decent habits and gives steady results back.

What size is the practical standard?

An 8-inch blade length is the practical standard for most home cooks. It’s versatile because it offers reach and control, especially on large produce like cabbage or melon, and it’s still manageable on smaller boards. In Japanese terms, it lines up closely with a 210 mm gyuto, which makes comparisons feel fair instead of fuzzy.

Shorter lengths like 180 mm can feel quick for tight spaces, while 240 mm shines in pro prep—more stroke length, fewer repeated cuts. But bigger blades also amplify poor habits, so the “standard” keeps winning because it’s forgiving while still capable.

What companion knives complete the set?

A chef knife can do almost everything—but not always comfortably, and not always safely. This is where smaller roles matter: a paring knife for in-hand work and tight trimming, a utility knife for medium tasks that feel clumsy under a full-sized blade, and a boning knife for working around joints and separating meat cleanly without wrecking your blade edge. A peeling knife also earns its keep for quick skin work when you want more control than a longer blade allows.

In practical kitchen terms, it often looks like this:

Chef knife (8-inch / 210 mm): daily prep, board work

Paring knife (75–100 mm): peeling, coring, detail trimming

Utility knife (120–150 mm): sandwiches, citrus, small veg

Boning knife (150–160 mm): poultry and meat breakdown

This isn’t about buying more knives for the sake of it. It’s about avoiding awkward cuts that twist an edge, crush a tomato, or make you fight the food instead of cutting it.

What does the forge teach about “Western” design?

In a Japanese bladesmithing shop, the contrast is physical: thin edges whisper, thicker edges thump. Traditional Japanese materials like tamahagane and fibrous wrought iron teach respect for transitions—how hardness, geometry, and grind meet without weird surprises. Pattern-welded damascus and forge-welded laminates can look dramatic, but performance still comes down to heat treat and geometry, not the pattern.

At MG Forge, making Japanese kitchen knives from steel through finishing keeps that lesson close. A robust Western-leaning profile can still benefit from Japanese discipline: clean heat treatment, consistent grinds, and a finish that doesn’t hide mistakes. The best knife feels simple because the complicated decisions were handled earlier.

How does sharpening and honing really differ?

Regular maintenance with a honing steel matters for keeping a Western chef knife sharp. Softer steel tends to roll before it chips, and that rolled apex often isn’t “dull steel”—it’s a bent edge. Honing realigns it, restoring sharpness and keeping the bevel behaving the way it should.

Western chef knives usually need more frequent honing, but they’re also easier to sharpen at home than harder steels. A quick routine—light hone during the week, proper sharpening when honing stops helping—keeps the blade predictable and keeps your cutting consistent instead of random.

What care habits prevent most damage?

To maintain Western chef knives, hand-wash and dry immediately. Avoid cutting on glass, ceramic, or granite; those surfaces can dull the blade edge fast and can chip a fine edge even on “durable” western knives. Those two habits alone prevent most of the “my knife suddenly got bad” mysteries.

Also worth repeating: a dull knife is more dangerous than a sharp one, because it needs more force and slips more easily. Care isn’t preciousness—it’s safety. Use a stable board, store the blade dry, and spend a few seconds on maintenance instead of grinding through tomatoes with brute force.

Where do buying decisions go wrong most often?

Balance, comfort, blade material, edge angle, and length all matter when choosing a chef knife, but most people get hypnotized by the steel label and forget the feel. A heavier knife can be great for power, yet too much weight can reduce control—especially for fine tip work or quick trimming.

Another common mistake is chasing extreme profiles. The blade shape shouldn’t be too extreme, because subtle curves reduce effort in repetitive chopping and make everyday cutting smoother. The best western style knives aren’t flashy; they’re the ones that match how you actually move.

What about famous Western brands in 2026?

Some brands became reference points for what western knives are “supposed” to feel like. Wüsthof is widely recognized as the best German knife company, and Wüsthof knives are precision-forged from a single piece of specially formulated German steel. With proper care and sharpening, Wüsthof knives are designed to last decades, and the Wüsthof Classic chef’s knife is often inherited and still used daily after decades.

Other widely discussed options include the Tojiro knife brand, which offers a variety of western style knives including chef knives and paring knives; the Tojiro chef knife is noted for its heft and sleek shape. The Misono UX10 is also highly regarded for a sharp edge and nimble form, while the Mercer Millennia is often recommended as an affordable, reliable, easy-to-use choice. Notes vary: Mac knives are known for sharpness but may dull more quickly than other brands, and some find Messermeister’s weight can make it difficult to control.

What is a western chef's knife?

A western chef’s knife is a general-purpose kitchen knife designed for slicing, dicing, chopping, and mincing. It typically has a symmetrical V-shaped edge with a double bevel and a more curved profile that supports rocking cuts. Many use softer stainless steel (often around 54–58 HRC), making them forgiving, tough, and easier to maintain with regular honing and sharpening.

What is the best Western chef knife brand?

Wüsthof is widely recognized as the best German knife company. Their knives are precision-forged from a single piece of specially formulated German steel and are designed to last decades with proper care and sharpening. That said, balance, comfort, and handle fit still matter as much as the logo for any chef knife.

What is the difference between Western and Eastern chef knives?

Western chef knives are generally heavier, thicker, and commonly use softer stainless steel that’s less prone to chipping. Japanese-style chef knives are often lighter with thinner, more precise blades, and frequently use harder high-carbon steel for sharper edges. Western profiles are usually more curved for rocking, while many Japanese designs favor straighter edges for push-cutting and cleaner slicing.

Who made Western brand knives?

Western-brand knives are made by a range of established manufacturers, often tied to European knives traditions and Japanese makers producing Western-style lines. Examples often mentioned include German makers like Wüsthof and Japanese brands offering Western-style patterns such as Tojiro and Misono. “Western” mainly describes the design approach—double-bevel geometry and a curved profile—more than one single origin or one factory line.

What design traits define the reliability of a western style chef knife?

A western style chef knife is valued in cutlery for a durable blade edge and robust geometry: thicker stock, a supportive tang, and a profile that can maneuver predictably through foods from herbs and garlic to dense produce, with techniques that tolerate daily board contact; while personal preference shapes whether weight and structure feel right, many users note it originated as a general-purpose pattern that holds a keen working edge without being too brittle, and in practice it is less likely to break under imperfect habits, a point often mentioned when contrasting europe-derived designs with japan-made thin grinds and when discussing how MG Forge applies consistent heat treat to create dependable results (fine; sign; carbon; hard).